What Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Really Protected

The military’s taboos around gayness paradoxically allowed it to remain one of the last bunkers of intimate male-bonding.

Before the ultimate repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell (DADT), there was a vocal, but powerful minority who were deeply resistant to ending the ban, such as former Senator and war hero John McCain and current Senator Lindsey Graham, along with military men like former Marine Commandant General Jim Amos and Air Force Chief of Staff General Norton Schwartz. Their voices were supported by other prominent individuals whose claims ranged from saying repealing DADT would “wreck the finest military force in the world” to the non-prominent, like Ann Coulter, who wondered if being openly gay in the armed forces would mean soldiers coming to morning drills dressed as Cher impersonators.

Why the division, the vitriol, the lame jokes? What exactly was Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell safeguarding? After all, the anger provoked can’t really be about protecting the sanctity of the group shower or preventing an explosion of foxhole confessions. So, why was it worth such energetic defending? Paradoxical though it may sound, what DADT actually ensured was that men would still have a place to experience male-male intimacy without it, or them, being called gay.

As recently as a hundred years ago, men talked about their love for each other freely. In fact, the desire for intimate fraternity was considered more than just normal for a male life; it was believed to be essential. Men acted on this desire without fearing prejudice or ridicule. Here’s a fairly common example from the 1830s, taken from the journal of Albert Dodd, a Yale student, about his friend John:

“I regard him, I esteem him, I love him more than all the rest…it is not friendship merely which I feel for him, or it is friendship of the strongest kind. It is heart-felt, a manly, a pure, deep, and fervent love.”

As open homosexuality emerged, however, it became masculinity’s foil, its antithesis. Men grew skittish about wanting to express sentiments like Dodd’s or participate in environments where fraternization could be equated with gayness. And so men stopped acting on their fraternal impulses, in spite of the fact that they did not go away.

In fact, quite the opposite has happened: The fear of being gay, effeminate, the anti-male—take your pick—has created a more intense, if repressed, longing in men to find and experience those rare environments where men can be close to other men without “forfeiting” their masculinity.

The fear of being seen as gay has created a more intense, if repressed, longing in men to find and experience those rare environments where they can be close to other men without “forfeiting” their masculinity.

Indeed, the prospect of losing a fortress as happily time-warped as the military is terrifying to men because it means one less “safe space” for real male bonding, not its sitcom version.

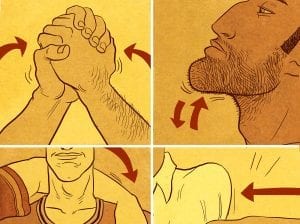

The military, after all, even with female soldiers, remains a model for this type of masculine environment. If nothing else, enlisting as a soldier makes one’s credentials as a man irrefutable. And those credentials offer a powerful alibi, or cover, for strong male connection. Soldiers can act on correcting the modern vacuum of male intimacy without paranoia or self-consciousness, without arousing prejudice or suspicion. They can pursue it with carefree gesture and intent and still be, in a word, men. Whether that pursuit occurs in the group shower, on the battlefield, or in more banal circumstances, hardly matters. What matters is that, in finally being available, this rarest of outlets isn’t taken away from men.

Ending DADT threatened this because in allowing even a hint of overt homosexuality into this community, a man must once more lead a paranoid, self-conscious existence. He must worry that natural bonding gestures could be misinterpreted by the code of 21st-century maleness, which says a man can’t make such gestures or have such intentions without being gay.

Men can’t, or won’t, say any of this.

We won’t point out that our version of manhood is more conservative than the one a hundred years before. Or that today’s manhood unfairly forces men to go without a full half of human intimacy. And not just any intimacy, but a pivotal kind: an intimacy that affirms one’s manhood by the only group who can—other men.

Instead, we’ll talk about the group shower, unit cohesion, foxhole flirtation rather than admit a more dangerous truth: We are desperate to protect those remaining environments that permit us to be close to each other without risking condemnation.

In Nathaniel Frank’s book on Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Unfriendly Fire, he wrote that Charles Moskos, the architect of the policy, “told lawmakers that the principal reason for the gay ban is to repress the homoerotic desire that is an inherent part of military culture.”

Inherent, but perhaps like many things in today’s masculinity, misconstrued.

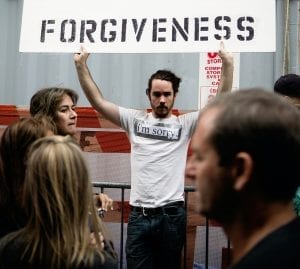

Homoeroticism might be how this particular repressed desire gets expressed, but intimacy is not the same thing as eroticism. We know that because, long before there was a taboo about gay love, there were men who loved each other enough to take a bullet for the other. Repealing DADT asks a very critical question for modern masculinity and the men who represent it: Are we brave enough to see love between one another as something we no longer need a battlefield to justify?